Author: Ludovica Zen

“Our cities are patriarchy written in stone, brick, glass and concrete” Jane Darke, 1996.

Two years ago on the 8th of March we were preparing for the first national lockdown in Italy, while today the town and city squares are again crowded for the International Women's Day.

Feminist demonstrations remind us of how important it is for women to appropriate their own space within the city: this is what feminist urban planning deals with. It’s a discipline that studies urban space from a gender perspective and proposes solutions for a democratic, inclusive city and, using the words of Leslie Kern, author of the essay "Feminist City" (2019), "non-sexist". Kern, from her own experience, analyses the relationship of women with urban space and how this often tends to disadvantage the female gender.

“My urban experiences are determined by my gender identity. My being a woman determines the way I move around the city, the way I live my life day after day and the choices at my disposal".

Leslie Kern, “Feminist City: Claiming Space in a Man-Made World”, Verso Books, 2019.

The city of women. Urban planning and feminism

8th of March 2022

reading time: 7 minutes

The kind of urban plot, the location of the different activities, the planning of the mobility of people, the design of public spaces, all this directly affects the lives of the city's inhabitants. These aspects are not random and not neutral, but often respond to the priorities and hierarchies of a system with a capitalist economic organization and a patriarchal social order structure. The aim of feminist urban planning is precisely to revise urban spaces to transform them and reprogram the priorities in favor of those who live there.

Women have always been looking for their own space, not only figurative, but also physical, outside the domestic environment to which they have been relegated for centuries.

In the book "The space of women" (“Lo spazio delle donne”, Einaudi, 2022), Daniela Brogi writes: "Our life is made up of situations in which words, actions, looks and bodies exist because they occupy certain spaces. […] If this is true in general, for women it is even more, because space in many cases has worked as a symbol of an imposed destiny ". These are women confined to private spaces, "hidden buildings, forgotten houses, secret gardens, rooms with windows, kitchens, attics, colleges, stables, cells of monasteries, sitting rooms and every other form of closed place, separated from the outside world".

In 1405 Christine de Pizan, the first woman writer and historian by profession, created a virtual women-only space in the book "The city of women", where they could live safe from violence and prevarication of men, by taking control of the public space and outside the dwelling.

1929 is the year of publication of the popular "A room of one's own", by Virginia Woolf, essay in which, through the metaphor of the room, the British writer affirms the need for the participation of the female gender in the world of culture, a traditionally male field.

Later, in 1977, the article "Female optics in architecture" appeared in Effe, a historical Italian magazine about the feminist movement, which deals with the importance of the appropriation of the discipline by women to "retrace the history of the territory, the city and the house, in search of the confinement place of one of the two protagonists: the woman". Gender segregation in domestic spaces, but also in certain public places, is translated in the modern city in terms of "hostility" which is experienced concretely through the "lack of spaces, services, overall of "freedom”” with respect to the needs of women.

The city reflects gender inequality: this is mainly due to the fact that great architects and urban planners are and have been mostly men, who have not been able to take into account the needs not only of women, but also of the different social categories and gender minorities. The fact of having more women architects, however, may not be enough to solve the problem, because the female gender itself has internalized the stereotypes of the male gaze and is struggling to get away from it. What can make a real difference is a re-reading of the urban environment and the organisation of its spaces.

Among the most serious issues that the male gaze has not taken into account in urban planning is certainly safety, or rather, the sense of insecurity perceived by women in some places and moments of life in the city. A global study by Hollaback!, a movement against street harassment, and Cornell University showed that more than 81.5% of European women were harassed on the street before the age of 17, but one worrying fact concerns Italy, where more than 88% of the women interviewed said they had changed the path to return home due to harassment. Poor lighting, little control and the lack of adequate transport, especially at night, promote the sense of fear that deprives women of the "right to the city", the right to feel safe in the space in which they live, in which a sort of map of the danger is born and it transforms according to the age or the time of day.

The organization of mobility, in fact, disadvantages the female gender, since urban transport focuses mainly on peak working hours, neglecting parts of the day, such as those in which children are taken to school or shopping, activities that are still often a prerogative of women. With the pandemic, the situation has worsened: many lines, especially those at night, are suspended and that’s a problem for many women who work during uncomfortable hours, often forcing them to pay for a taxi or to wait for longer in the dark and isolated.

Another issue concerns toilets, often lacking and inaccessible: how many times have we been faced with very long lines just in front of the women's bathroom? Some scholars propose the solution of gender neutral bathrooms, provided with all the necessary services for everyone, such as the changing table, of which very often the bathrooms lack. Motherhood is a crucial element for several reasons, just think of the mobility with the stroller in the city or the spaces for breastfeeding, that is often disadvantaged in public places. Statistically, in fact, it is precisely the woman who is mainly responsible for the care of sons and daughters.

Feminist urban planning has been developing on a theoretical level in the last few years, but some people have been promoting projects and solutions for a feminist metamorphosis of urban space.

The Col-lectiu Punt 6, a Catalan collective, has been working since 2005 to rethink the city's spaces from a gender perspective. Here’s the collection of the various projects carried out by the group, such as the project for the multifunctional, accessible and inclusive green space of Plaça de Sóller, in the Barrio de Porta of Barcelona, or the women's laboratory to integrate gender criteria in the Special Plan of the Parque de la Devesa of Girona (Catalonia). "Feminist Urbanism" (2019), a book published by Virus, collects the principles that guide the urban planning practice of Punt 6: the focus of the research of the collective is the daily life of the inhabitants of the cities, since only from their experience and involvement it is possible to create a space tailored to women. The contemporary city must therefore be "daily", designed from an interdisciplinary perspective through the criteria of proximity, vitality, diversity, autonomy and representativeness.

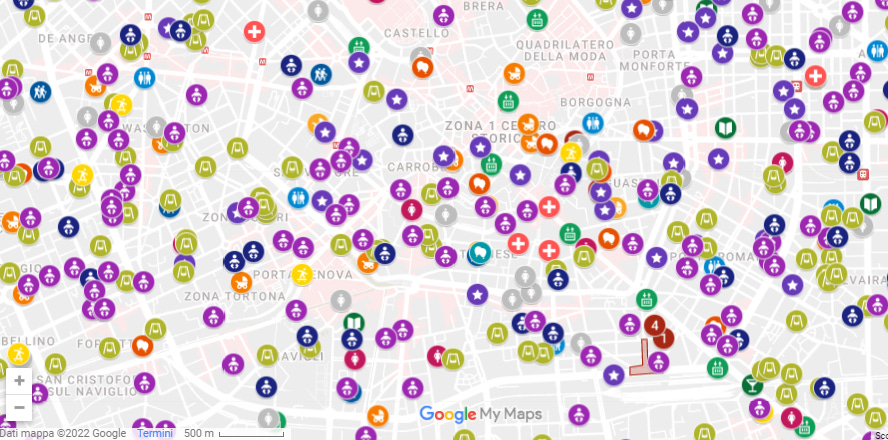

Back to Italy, the association Sex & The City Milano, through projects, meetings and research, promotes a gender reading of urban spaces that overcomes the dualisms of male-female, production-reproduction, public space-private space in urban planning. The project, curated by Florencia Andreola and Azzurra Muzzonigro, studies the uses of the city by women and gender minorities, the perception of insecurity in public space and the public representation of genres in toponymy, statuary and the titling of public buildings. This is a fact not to be underestimated: according to data from the Women's Toponymy Network, out of 4250 public spaces in Milan, only 141 are dedicated to women, mainly from the religious world. In January 2022, "Milan Gender Atlas" was released, a theoretical and practical atlas of the city that deconstructs contemporary urban space by observing it through the lenses of the genre with the aim of meeting the needs of women and minorities.

So let’s dedicate this 8th of March to the importance of architecture as a political gesture in and for urban space, especially now that inclusiveness plays such an important role in the public debate. Gender urban planning can really change the city by meeting the needs of those who live it.

If you’ve read this far… THANK YOU!

If you liked this post, why not share it?

and if you have any comments or suggestions, write us!

See you for the next Postcard!